Brilliant lights of Times Square

New York as a space of exposure

All the images in this post are by Manuela Conti, shot in Manhattan in 2010

After Florence and Berlin, my journey into global public space at the beginning of the 2000s turned to what clearly appeared to be the heart of the empire of the image. It was time to go back up the source of the culture industry and explore the effects on public space in the heart of the symbolic economy, in the home of the media and entertainment industry, the political matrix of financial globalisation - the time, in short, to tackle the skins and pavements of New York City. Here I arrived with the wound of ground zero still open and smouldering before my eyes, a smoking crater that was anything but metaphorical.

Unlike Berlin's, which is characterised by nuances and gradations, New York City's urban public space is the outcome of brutal dichotomies, the product of sharp contrasts between dialogic categories, starting with the opposition of two fundamental conceptions: business culture versus street life. If the urban idea of New York is ontologically connected with the space of business, the concept of street life is equally ingrained with it. Literature, jazz, (crime) news, and above all cinema, have conveyed to us an image of the city connoted by the modern experience of the moving crowd: a space of flow, congestion, saturation. The dichotomy is also expressed as a hiatus between the conceived city and the perceived city: on the one hand, the structural grid, a rigid and two-dimensional concept, which clearly marks the division between public and private spaces; on the other hand, the competition, the American dream, which is expressed in the incessant production of representations, conflicts, discourses, relations, values that arise in the public sphere and define public space essentially as the space of a public, the dominant and winning one.

The public dimension is here represented by the road, the infrastructure, the pavement - in the final analysis, it is the ideology of freedom of movement, which, however, remains subordinate to the optimisation and expansion of the private sphere, of business, of enterprise, individual or corporate. In this sense, the New York street differed profoundly from the ones I had walked on in Berlin: here, the pavement is a brutally functional space of circulation, antithetical and radically distinct from the private spaces, from which it is separated by diaphragms and clear and manifest control devices. Where Berlin presents inhabited walkways, which are articulated in different functions and penetrate into the blocks, connecting interstitial spaces, dissolving into public greenery and parks, generating different gradations of the public, the New York city pavement appears monotonous, composed of concrete slabs identical in every neighbourhood and for users from all classes: essentially ‘infrastructure’, it is a connective system that winds between different private and public properties, becoming a competitive terrain where the right to public life is disputed.

The discourse on public space in New York historically reflects such an exaggerated dichotomy. In these years, at the turn of the millennium, this was felt with particular acuity: the debate was dominated by two different, though not entirely incompatible, visions. On the one hand, there was the nostalgic vision, a literature of loss, as in Ted Kilian formulation1, which emphasised the disappearance of an alleged civic quality and an atavistic vocation of urban space as a place of contact and exchange. This literature, which originated in authors such as Jane Jacobs, William H. Whyte and Richard Sennett, had found a resurgence at the close of the millennium among critical American geographers and architects such as Don Mitchell, Michael Sorkin and Marie Christine Boyer. While the condemnation of the processes of discrimination and cancellation of discordant forms of life through the exasperated commodification, privatisation and military control of public space was at the centre of the critical literature, the nostalgic vision of ‘loss’ favoured also more accommodating and reformist logics, espousing in a quite natural way the design tendencies of new urbanism, which preached the revalorisation of centralities, the search for postmodern architectural solutions and, more generally, conservative instances with respect to urban public space. It is not surprising that this nostalgic refrain often ended up justifying processes of gentrification, displacement, segregation, becoming a tool for urban marketing operations and property development.

On the other hand, a ‘transitional’ thesis could be identified, giving rise to a trans-urbanism approach2, according to which the classical public space was being substantially reconfigured as a consequence of the social and anthropological evolutions of the information society, being arranged in a hybrid and fluid configuration, whereby the public remained exposed to the modulation of economic flows, information and transitions according to new technological determinants. This view was meant to be ‘realist’ with regard to the need to ‘prophylactically’ control the freedoms of use and movement in public space, in the face of phenomena such as terrorist threats, international migration, the potential spread of pathogens (AIDS and other warnings were already foreshadowing the successive waves of SARS, up to COVID-19), with veins of optimism about the effects of innovation and the socially corrective and economically redistributive potential of technology. This vision was ambiguous, with a double connotation: often dominated by a fascination with the incorporeal and semiotic essence of the emerging landscape, sometimes critical and concerned about the access and democratisation of a new frontier territory constituted by the expanding infosphere. These two visions converged paradigmatically in the place from which my journey into New York's urban space began, the dazzling scenery of Times Square.

The very form of Times Square represents the idea of crossing as the essence of North American public space. Unlike the European-style square, which emphasises the open space's function as a place of rest, meeting, and conciliation, the term square in American toponymy refers to a critical crossroads, the intersection of two major arteries. This logic is fully embodied, morphologically, in Times Square, which is literally a 'X', a dynamic space that exists architecturally by virtue of movement, flow, and change. Imagine Times Square without screens, lights, or traffic: it would literally fade. The crossroads of Broadway and 42nd Street is the landscape where those two discourses of public space intersected in the most emblematic way: it embodies the trans-urbanist vision tout court and is at the same time imbued with nostalgia. Times Square represents the ultimate vision of the overexposed city, a showcase for transnational corporate power and global media centres, but also an emblem of the erasure and sterilisation of the visceral, corporeal and erotic public life of a New York that once was. The beating heart of Manhattan, analogous to Berlin's Potsdamer Platz, Times Square has always been a central node in the cultural geography of New York, and perhaps of the entire American nation: the place where the arrival of the New Year is celebrated, the centre of the entertainment, show business and media district. It was born as a press district, as the name itself reminds us: the New York Times, destined to become one of the leading national (now global) newspapers, opened its headquarters here in 1904. At the time, the area was a suburb frequented by prostitutes, the heart of the theatre district, a historical site of vaudeville, but also a district of vice, of off culture, of pornography, thus, a cornerstone of queer and LGBT geography. All the contradictions between puritanism and moral ease of the nation contained in one place, in a paradigmatic dialectic between the ethics of money and the morality of sex.

Times Square has always represented the very essence of New York public life, characterised by euphoric hyperactivity, density, diversity of offerings, the Simmelian promise of anonymity and intensified nervous stimulation. Since the 1980s, Times Square has been the subject of a series of policies and investments aimed at redeveloping one of the city's most visceral and controversial spaces into a global entertainment space. The ‘san(t)ification’ of Times Square took place through a drastic process that led to the erasure of many souls and qualities of the place. A process in which the Disney Corporation played a parallel role to that of the repressive-military zero-tolerance policies advocated by Mayor Giuliani, establishing a laboratory of neo-liberal urbanism of planetary avant-garde, where the Business Improvement District model and the total privatisation of local services - even in the administration of justice - was pioneered. The most obvious, epidermal aspect of this process is found in the exponential multiplication of screens that qualify the place as a global media device. As Marie Christine Boyer writes, Times Square ‘is regulated by guidelines requiring a minimum number of LUTSes (Light Units of Times Square) and controlled by planners who have planned for its spontaneous non-planning’.3 A 1987 ordinance determines the minimum quantity of light points that the surfaces of buildings facing onto the square must have: not, therefore, a restrictive prescription, but an incentive regulation, aimed at increasing the advertising potential of the urban surface. Here we find another suggestive exemplification of that planar shift from the horizontal to the vertical dimension of urban surfaces, as planning the city moves from lots to “LUTS”.

Naturally, such a logic gives the big advertising agencies and multinational corporations dominion over the image of this part of town. The concentration of liquid crystal screens and electronic displays supports the broadcasting of a continuous and dazzling stream of advertising and news, resulting in the programming of a veritable audiovisual palimpsest. The architectural form of the square has more to do with the concept of television or multimedia communication than with the traditional volumetric and monumental expression of a city, where the static stone surfaces are replaced by the flow of images and textual information of the electronic interface. The modern skyscraper, with its passive glass surfaces reflecting the movement of the city outside and displaying in translucence the frenetic activities of the office interior, had anticipated the self-celebration of capitalist performance, but still did so by celebrating the presence of the human factor concentrated within. In its new guise, however, the concept is surpassed by the active surfaces, which conceal the real content of the building and project aggressive representations of the powers that be, totally unrelated to reality, projecting data and images that converge here from everywhere - or, from nowhere. Large entertainment and communication corporations such as Disney, Warner Bros. and Viacom, whose spectacular information management and marketing practices tend to merge more and more into the concept of infotainement, dominate the landscape through impressive advertising narratives.4 The Reuters news agency building, whose façade is an immense text display, broadcasts agency launches from all over the world, while a few rows below scroll the world's stock exchange quotations: a continuous pulsation of events, names and figures that, alternating according to the randomness of the moment, are strikingly reminiscent of William Burroughs' cut-up literary experiments, or Ballard's prophetic science fiction in The Atrocity Exhibition. The Nasdaq Info Center houses a large television studio on the ground floor from which financial news is broadcast: the speaker speaks to the cameras and a large window through which passers-by can watch live from the pavement. From Times Square a stream of information is broadcast live from everywhere, while Times Square itself appears live all over the world at all times: dozens of cameras stream images of the square, effectively turning urban life into a global real-time show.

Traditional architectural values such as solidity, continuity, reliability, and gravity have been replaced by a glittering rhetoric of change, speed, brilliance, and the ecstasy of ubiquity. Times Square is the prototypical city-palimpsest, in which the materiality of the landscape is transformed into a programmed succession of images transmitted by screens, a mediascape dedicated to optimising the functions of space of exposure and space of circulation. One can only remain exposed to the constant flow of images and information - no stasis, no slowing down is possible in the cinematic city: the hyperkinetic narrative of Times Square thus stages the ecstasy of contemporaneity. The concept of cinematic urbanism that was forming in my argument about global public space was evident here, substantiated and tangible in the luminous and phantasmagorical articulation of the screens. It is a vertical articulation of urban space that is essentially ‘oculo-centric’, to use a category of Virilio's, which involves a violent reorganisation of the horizontal dimension and the lived and material space of the city. But behind the brilliant explosion of electronic rhetoric that has covered Times Square, an entire world has been erased. I won't dwell too much on the extensive critical literature that has analysed the contradictions, arbitrariness and violence of the removal processes that have taken place in the course of two decades of redevelopment policies - one of the most widespread and well-known debates in the field of urban studies - but it should be noted that, in the combination of the enormous concentration of financial interests and the immense visibility of the global urban district par excellence, this accelerated condensation of the American city has become a training ground and laboratory for most of the neoliberal urban policies to come. Almost all of the themes that characterise the urban debate of the last decades find their way into this context: from the privatisation of management functions and public safety to the privacy and control of citizens, from exclusion and social inequality to the preservation of a discordant heritage of marginal cultures, to the theme of the monopoly of information channels.

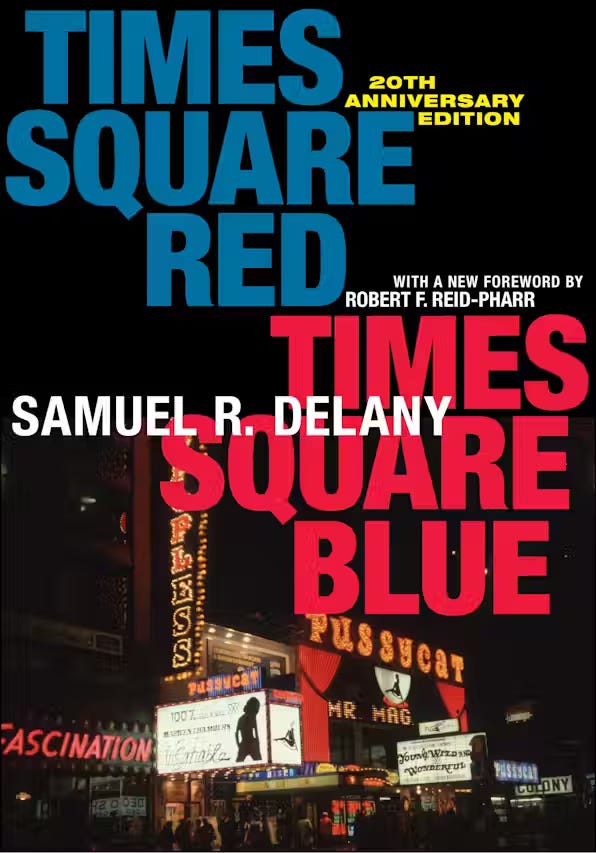

Central to the debate on urban transformations here is the question of exclusion/inclusion processes affecting weak and marginalised subjects. The individual's right to diversity, especially that pertaining to the sexual sphere, is a prominent issue. Bart Eeckhout, for example, in his article entitled ‘The Postsexual city? Times Square in the Age of Virtual Reproduction', tells the story of this transformation from the perspective of the desexualisation of Times Square, capturing the puritan tendency towards the public representation of a sexuality purged of any deviant connotations. Of all the vast literature that touches on this theme, the one who has perhaps succeeded in recounting it in the most profound, painful and immersive manner is once again a science fiction writer, Samuel R. Delany. It is in the essay Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, with a clear autobiographical slant, that Delany uses his identity as an African-American and homosexual heretic to recount the violent transformation the place underwent.

The process of moralizing and electronic redevelopment of Times Square is actually the façade narrative behind a process that has brought back into the hands of big business the almost total control not only of expression and communication, but also of the security management of public space as well as urban design. The story of the transformation of Times Square is often traced back to Rudolph Giuliani's campaign for security made famous by the concept of zero tolerance, but in fact the process started as early as the 1980s during the Koch administration, promoted by two main public actors, New York State's Urban Development Corporation and the City's Public Development Corporation.5 Through heavy tax cuts, private investments are attracted, while expropriations of marginal operators, demolitions and expulsions of small businesses accompany the operation. By 1992 over 200 businesses, most of them related to the sex industry, are closed or relocated. Residents' resistance is timidly expressed against the prospect of the arrival of the big entertainment multinationals. Walt Disney is the first to make a move, agreeing to renovate the historic Amsterdam Theatre on West 42nd, an operation for which he gets a low-interest loan of $26 million from the city government, and only has to invest $8 million of his own in the operation. Similarly financially supported by funds from the Koch administration, in the 1980s it was the insurance company Prudential that acquired land in Times Square. Already we see appearing a pattern that has become infamous today, in which masked by neo-liberal adulation towards private initiative we find a substantial financial incentive of public funds directed to monopolistic concentrations instead of supporting diversity and distributing resources to the weakest. The subsequent administration allocated another $35 million of municipal funds for expropriation operations in 1993. Other private investors arrived, including Viacom, Bertelsmann, and Morgan Stanley, who purchased real estate, supported by over $100 million in incentives from the state and municipal administration. The concentration and internationalisation that characterised these operations had the effect of creating free-trade zones within the territorial sovereignty of the city, and with substantial effects on the public space at the centre of these deregulated business projects. Saskia Sassen observes that the appeal that such highly valorised spaces exert on certain political and economic actors stems from their denationalisation and deregulation, spaces that are hijacked by liberalist economic projects.6 In the process taking place in Times Square in the 1990s, the State and the City of New York assume a prominent role in legitimising growth and strengthening of the global economy, but as agents of implementation of global processes, they in turn emerge weakened. The main instrument for the adoption of such models in New York were the Business Improvement Districts (BIDs), which found an extraordinary pilot in Times Square.

Besides being an extreme example of a spectacular public space in the global city, Times Square is in fact also a remarkable case of the then emerging urban management policies of special tax districts, where investors and landowners voluntarily tax themselves to maintain and enhance public spaces by taking these areas under their direct control. The Times Square Business Improvement District was established in 1992 to make Times Square ‘clean, safe and friendly’. It was founded and initially directed by Arthur Sulzberger Jr., at the time publisher of the New York Times, with a budget at the time of $6 million (today the figures are around $22 million). BIDs take over local governance functions by taking them over from public management, provide services such as maintenance and cleaning, public safety, visitor services and marketing, and invest financially in improvements and beautification in the designated area. Any commercial, retail or industrial area can apply for BID status and must be approved by the Community Board of the city planning commission, the city council and the mayor. At the time of my first visit to New York there were 40 active BIDs; as I write 20 years later there are 72. I may come back on the BID model in a future post.

Times Square tells in an exemplary manner how the process of economic globalisation has transformed the concept of public space, inducing a progressive withdrawal of the traditional organs of city and state government both from the planning of urban transformation and from the management of the territory, relocating them in a role of mere facilitation between strong economic actors committed to investing and attracting the ‘public’ (in the sense of consumers and audience) in areas strongly controlled by private capital. Moreover, a strong deregulation of the obligations of the major economic actors is matched by an inverse intensification of restrictive regulations on the civil liberty of the individual-citizen. This occurs, for instance, through the adoption of regulations focusing on the public management of private spaces rather than on universal rights of access to public space, and through the employment of private workers instead of civil servants to enforce these regulations.

In Times Square, I discovered the perfect embodiment of the new concept of public space that I had been theorising since my early explorations: the global space of exposure, an urban space created for and by the circulation of images in front of people, and at the heart of a larger shift to a new form of spatial production, which I proposed to call cinematic urbanism.

In the following post, I will move from the street to the library to review some sparse literature that is consistent with the concept of cinematic urbanism, after this long sensory excursion across the public space of three cities at the dawn of the 21st century. Meanwhile, let me conclude with a cinematic clip shot in Times Square in 2010 emblematic of the intertwining of media and military industries in the empire of images. Shot and edited by Jo Pixel / ogino:knauss, music Huge Voodoo, Mike Ladd.

Ted Kilian, “Public and Private, Power and Space”. In Andrew Light & Jonathan M. Smith (Eds.) The Production of Public Space. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers 1998.

Arjen Mulder, Joke Brouwer, Philip Brookman (Eds.) Transurbanism. V2 P̲ublishing/NAI Pub 2002.

Marie Christine Boyer “The Double Erasure of Times Square” in P. Madsen, R. Plunz (eds.) The urban Lifeworld. Formation, Perception, Representation. Routledge 2002.

I refer here to the corporate actor landscape observed in 2002-2003, which has of course evolved with the accelerated metabolism of big financial capital over a twenty-year period. Today, the visual prominence includes actors such as Netflix, Amazon, Apple etc. but the substance has not changed.

Sophie Body-Gendrot “Fragmentation of cities: local responses in New York and Paris” in Ghent Urban Studies Team (eds.) Post ex sub dis : urban fragmentations and constructions. 010 Publishers 2002.

Saskia Sassen Losing Control?: Sovereignty in an Age of Globalization. Columbia Univesrity Press 1996.